Lyon County, Kentucky

GEOLOGIC HAZARDS

Many concealed and exposed

faults are located throughout Lyon

County. Currently, there

is no evidence that these faults are active. Because of the proximity of Lyon County

to the New Madrid Seismic Zone, however, strong earthquake activity is a

possibility. Soil creep, slumps, and landslides along steep slopes may occur

from erosion or ground motion associated with a strong earthquake.

Areas associated with

saturated alluvium (unit 1) and other unconsolidated deposits (units 2 and 3)

are subject to liquefaction during a strong earthquake. Alluvium deposits are

also subject to flooding. Soils derived from alluvium deposits have a moderate

to high shrink-swell capacity, which may affect structural foundations and roads.

Flood information is available from the Kentucky Division of Water, Flood Plain

Management Branch, www.water.ky.gov/floods/.

Sinkholes are common in Lyon County.

Generally, sinkholes begin as small depressions like the one pictured above,

which is about 3 feet in diameter. While planting or harvesting at the Western Kentucky Correctional

Complex, tractors often run over these depressions, which then collapse,

causing the tractor to become stuck. Photo by Glynn Beck, Kentucky

Geological Survey.

Sinkholes and soil erosion are two major

issues to consider in land-use planning in Lyon County.

Both are encountered at the Lee

Jones Lyon

County Recreational

Park. The above baseball

field is being moved because of the formation of a small sinkhole in the old

infield (top right center). Also, soil erosion is occurring along rocked

drainages (foreground). Photo by Glynn Beck, Kentucky

Geological Survey.

About karst

More about karst

U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers bank stabilization project along the Cumberland River in Lyon and Livingston Counties. Photo

by Glynn Beck, Kentucky Geological Survey.

EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS

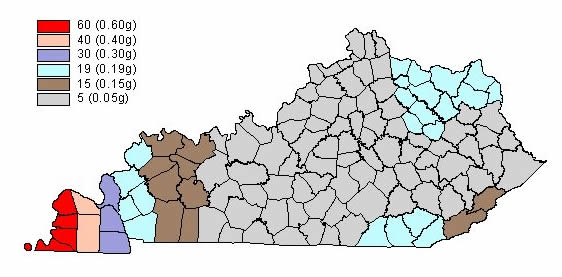

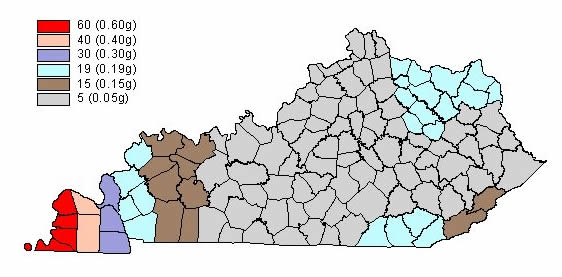

Peak ground acceleration at

the top of rock that will probably occur in the next 500 years in Kentucky

Although we do not know when

and where the next major earthquake will occur, we do know that an earthquake

will cause damage. Damage severity depends on many factors, such as earthquake

magnitude, the distance from the epicenter, and local geology. Information on

earthquake effects is obtained by monitoring earthquakes and performing

research. Such information is vital for earthquake hazard mitigation and risk

reduction.

The most important

information for seismic-hazard mitigation and risk reduction is ground-motion

hazard. One way of predicting ground-motion hazard is by determining the peak

ground acceleration (PGA) that may occur in a particular timeframe. The map

above shows the PGA at the top of bedrock that will likely occur within the

next 500 years in Kentucky

(Street and others, 1996). It shows, as expected, that PGA would be greatest in

far western Kentucky

near the New Madrid Seismic Zone. Ground-motion hazard maps for the central United States

and other areas are available from the U.S. Geological Survey. These maps are

used to set general policies on mitigating damage. For example, maps produced

by the USGS in 1996 were used to determine seismic design in building codes.

For additional information pertaining to earthquake hazards visit the Kentucky

Geological Survey website at www.uky.edu/KGS/geologichazards/geologichazards.html.

GROUNDWATER

Wells in the Ohio River alluvium yield several hundred gallons per

minute; compound horizontal wells have a potential yield as high as 5,000

gallons per minute. In most of Livingston

County, drilled wells in

the uplands are adequate for a domestic supply. Yields as

high as 50 gallons per minute have been reported from wells penetrating large

solution channels or fault zones. In the low-lying areas along the Cumberland and Tennessee

Rivers and the tributaries to the Ohio River, most wells are inadequate for domestic use,

unless the well intercepts a major solution opening in the limestone, and then

the yield could be very large. In the uplands of the southern section of the

county, between the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, most wells in gravel do not

yield enough water for a domestic supply. Springs with flows ranging from a few

gallons per minute to 177 gallons per minute are found in the county. Minimum

flow generally occurs in early fall; maximum flows in late winter. For more

information on groundwater in the county, see Carey and Stickney (2001).

Barnett Spring is a karst

spring, which flows year around. Karst springs are

common throughout Lyon

County. Photo by Glynn Beck,

Kentucky Geological Survey.

Land and Water

An example of the gently

rolling topography in Lyon

County, which is

excellent for row crop agriculture. Other parts of Lyon County

may have steep slopes with narrow valleys. Photo by Glynn Beck, Kentucky

Geological Survey.

Kuttawa Marina is

one of three marinas on Barkley Lake in Lyon

County. The other two

marinas are the Eddy Creek Marina and the Buzzard Rock Marina. Photo by Glynn Beck,

Kentucky Geological Survey.