Livingston County, Kentucky

GEOLOGIC HAZARDS

Many concealed and exposed

faults are located throughout Livingston

County. Currently there

is no evidence that these faults are active. Because of the close proximity of Livingston County to the New Madrid Seismic

Zone, however, strong earthquake activity is a possibility.

Soil creep, slumps, and

landslides along steep slopes may occur from erosion or ground motion

associated with a strong earthquake. Areas associated with alluvium material

are subject to liquefaction during a strong earthquake. These areas are also

subject to flooding. Soils derived from alluvium deposits have a moderate to

high shrink-swell capacity, which may affect structural foundations and roads.

Flood information is available from the Kentucky Division of Water, Flood Plain

Management Branch, www.water.ky.gov/floods/.

As seen in this picture, lowing lying areas

along the Ohio, Cumberland,

and Tennessee Rivers,

in Livingston County, are prone to flooding. During the 1997 flood, Ohio River flood water was 3.5 feet deep in this house.

(Photo courtesy of Sheena Thomas- Brown, Livingston County

4-H/Youth Development Agent.)

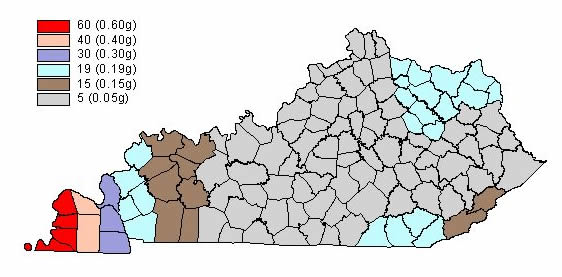

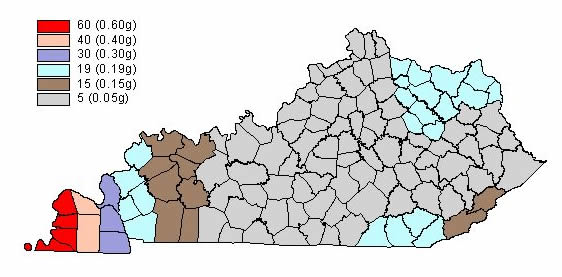

EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS

Peak ground acceleration at

the top of rock that will probably occur in the next 500 years in Kentucky

Although we do not know when

and where the next major earthquake will occur, we do know that an earthquake

will cause damage. Damage severity depends on many factors, such as earthquake

magnitude, the distance from the epicenter, and local geology. Information on

earthquake effects is obtained by monitoring earthquakes and performing

research. Such information is vital for earthquake hazard mitigation and risk

reduction.

The most important

information for seismic-hazard mitigation and risk reduction is ground-motion

hazard. One way of predicting ground-motion hazard is by determining the peak

ground acceleration (PGA) that may occur in a particular timeframe. The map

above shows the PGA at the top of bedrock that will likely occur within the

next 500 years in Kentucky

(Street and others, 1996). It shows, as expected, that PGA would be greatest in

far western Kentucky

near the New Madrid Seismic Zone. Ground-motion hazard maps for the central United States

and other areas are available from the U.S. Geological Survey. These maps are

used to set general policies on mitigating damage. For example, maps produced

by the USGS in 1996 were used to determine seismic design in building codes.

For additional information pertaining to earthquake hazards visit the Kentucky

Geological Survey website at www.uky.edu/KGS/geologichazards/geologichazards.html.

GROUNDWATER

Wells in the Ohio River alluvium yield several hundred gallons per

minute; compound horizontal wells have a potential yield as high as 5,000

gallons per minute. In most of Livingston

County, drilled wells in

the uplands are adequate for a domestic supply. Yields as

high as 50 gallons per minute have been reported from wells penetrating large

solution channels or fault zones. In the low-lying areas along the Cumberland and Tennessee

Rivers and the tributaries to the Ohio River, most wells are inadequate for domestic use,

unless the well intercepts a major solution opening in the limestone, and then

the yield could be very large. In the uplands of the southern section of the

county, between the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, most wells in gravel do not

yield enough water for a domestic supply. Springs with flows ranging from a few

gallons per minute to 177 gallons per minute are found in the county. Minimum

flow generally occurs in early fall; maximum flows in late winter. For more

information on groundwater in the county, see Carey and Stickney (2001).

Limestone springs, such as Gum Spring

pictured above, are located throughout Livingston County.

Most of these springs flow year around and are used as drinking-water sources. Photo by Glynn Beck,

Kentucky Geological Survey.

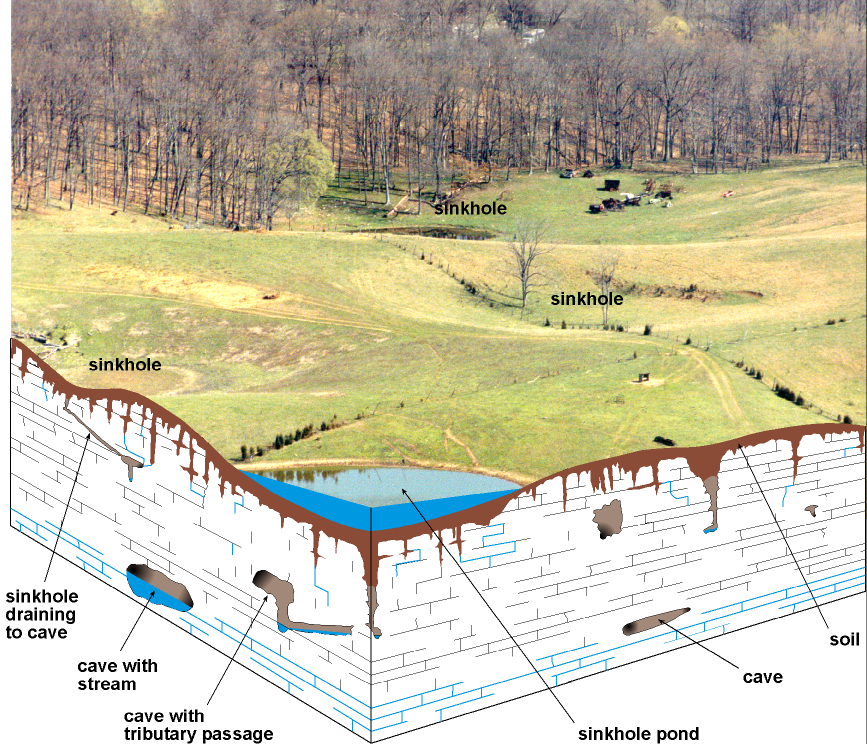

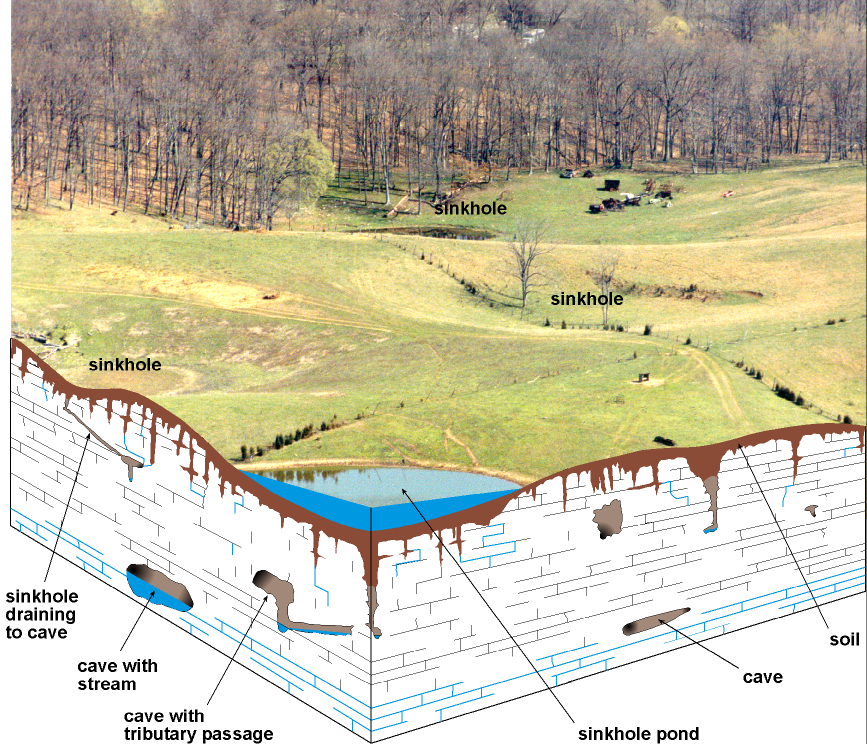

KARST

Never use sinkholes as dumps. All waste, but

especially pesticides, paints, household chemicals, automobile batteries, and

used motor oil, should be taken to an appropriate recycling center or landfill.

Make sure runoff from parking lots, streets, and other

urban areas is routed through a detention basin and sediment trap to filter it

before it flows into a sinkhole.

Make sure your home septic system is working properly

and that it's not discharging sewage into a crevice or sinkhole.

Keep cattle and other livestock out of sinkholes and

sinking streams. There are other methods of providing water to livestock.

See

to it that sinkholes near or in crop fields are bordered with trees, shrubs, or

grass buffer strips. This will filter runoff flowing into sinkholes and also

keep tilled areas away from sinkholes.

Construct waste-holding lagoons in karst areas carefully, to prevent the bottom of the lagoon

from collapsing, which would result in a catastrophic emptying of waste into

the groundwater.

If required, develop a groundwater protection plan

(410KAR5:037) or an agricultural water-quality plan (KRS224.71) for your land

use.

(From Currens, 2001)

Sinkholes are common karst

features throughout Livingston

County. Sinkholes

commonly form in row crop fields as small openings, 1 to 2 feet in diameter, as

seen above. Without proper management, these sinkholes can form depressions

that are tens of feet in diameter. Photo by Glynn Beck, Kentucky

Geological Survey.

Sinkholes

are natural drainage points for groundwater and should never be used as trash

dumps. One way to protect sinkholes is by using geosynthetic

materials and rip-rap, which help to control further soil erosion. Pictured

above is a sinkhole that has been protected on the T.L. Maddux

Farm in Livingston

County. This sinkhole

protection was funded by the Kentucky Soil Erosion and Water Quality Cost Share

Program through the Livingston County Conservation District. Photo

by Glynn Beck, Kentucky Geological Survey.

About karst

More about karst

RESOURCES

The 40-year-old Barkley Dam, constructed by

the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, provides flood protection along the Cumberland River,

and produces hydroelectric power. Barkley Dam has a generating capacity of 148

megawatts. Photo by Glynn

Beck, Kentucky

Geological Survey.

Limestone

is an abundant rock in Livingston

County. Currently, there

are two active limestone quarries in Livingston

County; Vulcan Materials

Reed Quarry (pictured above) and Martin Marietta Aggregates' Three Rivers

Quarry. Combined, these companies employ approximately 350 people and produce

approximately 13 million tons of crushed stone per year. Photo

by Glynn Beck, Kentucky Geological Survey.