Jefferson County,

Kentucky

KARST GEOLOGY

The term "karst" refers to a landscape characterized by

sinkholes, springs, sinking streams (streams that disappear underground), and

underground drainage through solution-enlarged conduits or caves. Karst landscapes form when slightly acidic water from rain

and snow-melt seeps through soil cover into fractured and soluble bedrock

(usually limestone, dolomite, or gypsum). Sinkholes are depressions on the land

surface where water drains underground. Usually circular and often

funnel-shaped, they range in size from a few feet to hundreds of feet in

diameter. Springs occur when water emerges from underground to become surface

water. Caves are solution-enlarged fractures or conduits

large enough for a person to enter.

In metropolitan areas where residential

construction is common, care must be taken to ensure that septic systems are

correctly installed to avoid polluting local streams and groundwater. In

WATER QUALITY

The Floyd’s Fork Creek

drainage basin contains a mapped wetland area in east-central

SOURCE-WATER

PROTECTION AREAS

Source-water

protection areas are those in which activities are likely to affect the quality

of the drinking-water source. For more information, see

kgsweb.uky.edu/download/water/swapp/swapp.htm.

CONSTRUCTION MATERIALS

The Kosmos

Cement Plant was founded in 1905, and the nearby community of Kosmosdale (formerly Riverview) was named after the

plant. About 720,000 tons of cement are produced by the plant annually.

RIVER TRAFFIC

River traffic influences

land use in

FLOODING

A 29-mile long system of

flood walls, gates, pumping stations, and levees allows for multiple land uses

in the Louisville-metro area. The flood walls were constructed following the

1937 flood when the river crested at 85.4 feet.

Growth of

the metropolitan

SLOPE STABILITY

Drainpipes

and limestone riprap are used along the shale slopes of the Muldraugh

Escarpment to help prevent water infiltration and subsequent slope instability

onto the Gene Snyder expressway. Photograph by Bart Davidson,

EROSION CONTROL

During

construction, erosion-control fences such as these may be needed to prevent

silt from entering local streams. Photo by Bart Davidson,

Riprap

drainage control and erosion protection. Photo by Stephen Greb,

POWER PRODUCTION

Large

cities such as

A sister

power station to Mill Creek, the Cane Run Power Station burns 1.3 million tons

of coal per year, all shipped by rail. The plant produces gypsum as a

by-product that must be disposed of in environmentally safe landfills. Photograph by Steve Greb,

GROUNDWATER

The alluvium along the

Water is hard or very hard

but otherwise of good quality. Groundwater in upland areas may contain salt or

hydrogen sulfide, especially at depths greater than 100 feet.

For more information on

groundwater in the county, see Carey and Stickney (2001).

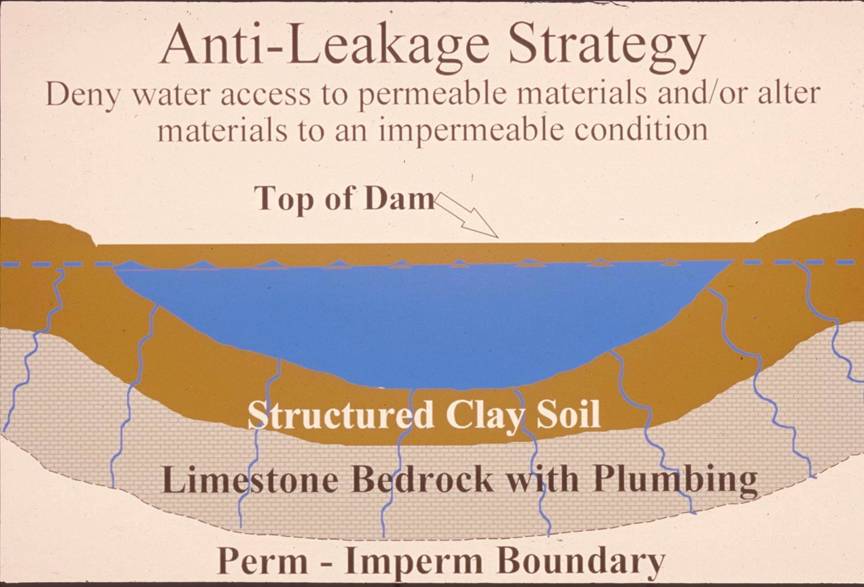

POND CONSTRUCTION

Successful pond construction

must prevent water from seeping through structured soils into limestone

solution channels below. A compacted clay liner, or artificial liner, may

prevent pond failure. Getting the basin filled with water as soon as possible

after construction prevents drying and cracking, and possible leakage, of the

clayey soil liner. Ponds constructed in dry weather are more apt to leak than

ponds constructed in wet weather. Illustration by Paul

A pond liner consisting of

clayey soil is placed in loose, moist layers and compacted with a sheepsfoot roller. A geotechnical engineer or geologist should

be consulted about the requirements of a specific site. Other leakage

prevention measures include synthetic liners, bentonite,

and asphaltic emulsions. The

Dams should be constructed

of compacted clayey soils at slopes flatter than 3 units horizontal to 1 unit

vertical. Ponds with dam heights exceeding 25 feet, or pond volumes exceeding

50 acre-feet, require permits. Contact the

CITY OF

Situated on the Ohio River,