Major Construction

An

understanding of the geology of an area can help prevent costly construction failures.

Constructing this road in

Pond Construction

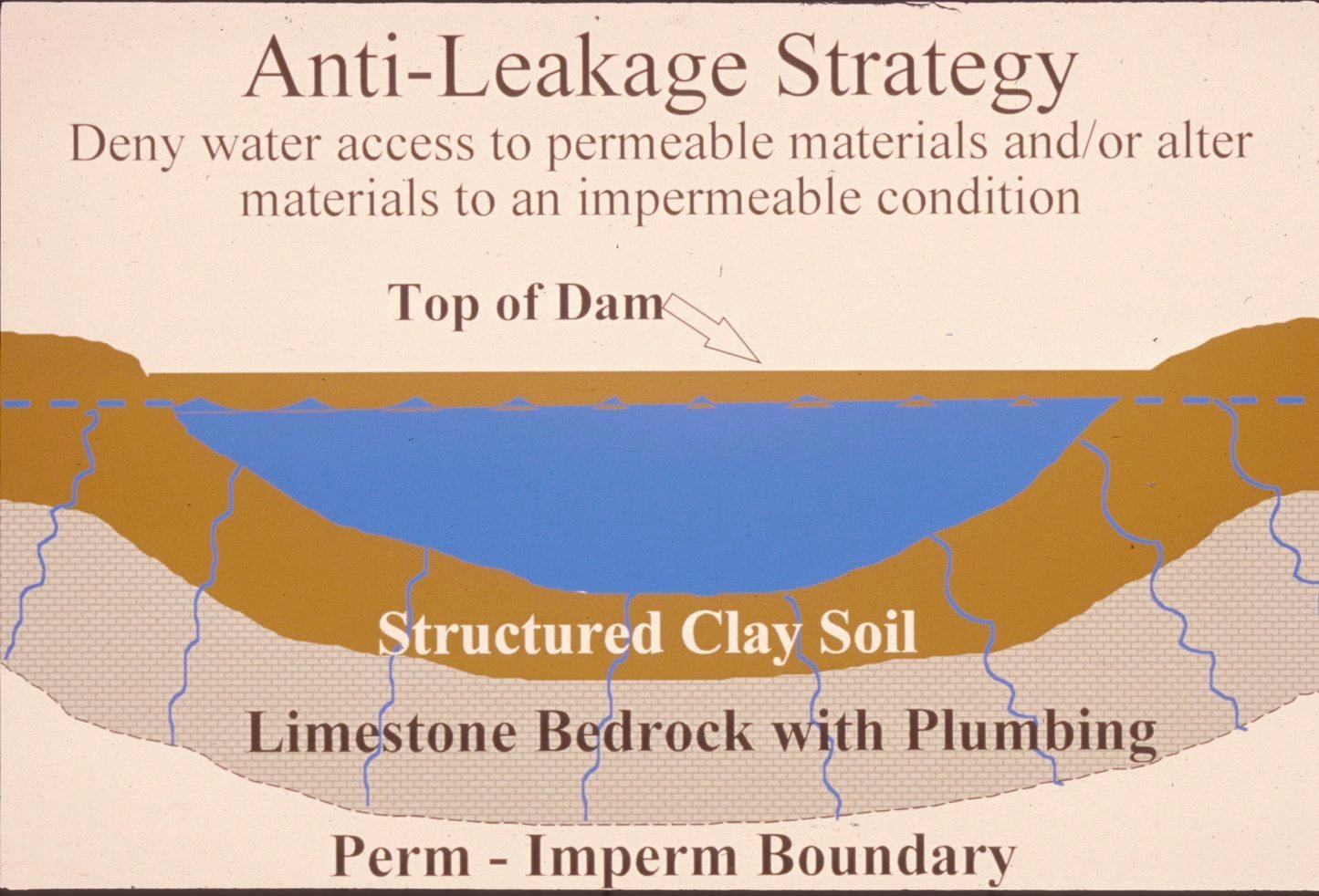

Successful

pond construction must prevent water from seeping through structured soils into

limestone solution channels below. A compacted clay liner, or artificial liner,

may prevent pond failure. Getting the basin filled with water as soon as

possible after construction prevents drying and cracking, and possible leakage,

of the clayey soil liner. Ponds constructed in dry weather are more apt to leak

than ponds constructed in wet weather. Illustration and

discussion by Paul Howell, USDA-NRCS.

A

clayey-soil pond liner is placed in loose, moist layers and compacted with a sheepsfoot roller. A geotechnical engineer or geologist

should be consulted regarding the requirements of a specific site. Other

leakage prevention measures include synthetic liners, bentonite,

and asphaltic emulsions. The U.S. Department of

Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service can provide guidance on the

application of these liners to new construction, and for treatment of existing

leaking ponds. (photo and discussion by Paul Howell,

USDA-NRCS)

Dams

should be constructed of compacted clayey soils at slopes flatter than 3 units

horizontal to 1 unit vertical. Ponds with dam heights exceeding 25 feet, or

pond volumes exceeding 50 acre-feet, require permits. Contact the Kentucky

Division of Water,

Environmental Protection

- Never use sinkholes as dumps.

All waste, but especially pesticides, paints, household chemicals,

automobile batteries, and used motor oil should be taken to an appropriate

recycling center or landfill.

- Make sure runoff form parking

lots, streets, and other urban areas is routed through a detention basin

and sediment trap to filter it before it flows into a sinkhole.

- Make sure your home septic

system is working properly and that it's not discharging sewage into a

crevice or hole.

- Keep your cattle and other

livestock out of sinkholes and sinking streams. There are other methods of

providing water to livestock.

- See to it that sinkholes near

or in crop fields are bordered with trees, shrubs, or grass "buffer

strips." This will filter runoff flowing into sinkholes and also keep

tilled areas away from sinkholes.

- Construct waste-holding

lagoons in karsst areas carefully, to prevent

the bottom of the lagoon fromcollapsing, which

would result in a catastrophic emptying of waste into the groundwater.

- If required, develop a

ground-water protection plan (410KAR5:037) or an agricultural

water-quality plan (KRS224.71) for your land use. (From Currens, 2001).

Geologic

Hazards

Karst sinkholes

are common features in

Limestone terrain can be subject to subsidence

hazards, which usually can be overcome by prior planning and site evaluation. "A" shows construction above an open cavern, which later

collapses. This is one of the most difficult situations to detect, and

the possibility of this situation beneath a structure warrants insurance

protection for homes built on karst terrain. In

"B," a heavy structure presumed to lie above solid bedrock actually

is partially supported on soft, residual clay soils that subside gradually,

resulting in damage to the structure. This occurs where inadequate site

evaluation can be traced to lack of geophysical studies and inadequate core

sampling. "C" and "D" show the close relationship between

hydrology and subsidence hazards in limestone terrain. In "C", the house

is situated on porous fill (light shading) at a site where surface and

groundwater drainage move supporting soil (darker shading) into voids in

limestone (blocks) below. The natural process is then accelerated by

infiltration through fill around the home. "D" shows a karst site where normal rainfall is absorbed by subsurface

conduits, but water from an infrequent heavy storm cannot be carried away

quickly enough to prevent flooding of lowlying areas.

(Adapted from American Institute of Professional Geologists,

1993.)

Other

Hazards

Faults are common geologic structures across

Soil creep, slumps, and landslides occurring along

steep slopes may occur from erosion or ground motion associated with a strong

earthquake.

Areas associated with alluvium are subject to liquefaction

during a strong earthquake event. These areas are also subject to flooding.

Soils derived from alluvium deposits may have a

moderate to high shrink swell capacity, which may affect structural foundations

and roads.

Radon gas can be a local problem, although it is not

widely distributed in

RESOURCES

Groundwater

In karst areas such as

southern and eastern

In this highly karstic,

limestone rich county, most of the drilled wells in

the southern half of

Surface

Water

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed the Nolin River Dam in 1959 to prevent flood damage along the Nolin and

This levee was constructed to control flooding along

the Big Reedy Creek drainage in

Houchins Ferry

(above) is one of two ferries within

Energy

As demonstrated in this picture, oil well "pump

jacks" (foreground) and tanks (background) are a familiar site to

residents in

REFERENCES

American

Carey,

Daniel I., and Stickney, John F., 2001, Ground-water resources of

Currens, James C., 2001, Protecting Kentucky's Karst

Aquifers from Nonpoint-Source Pollution: Kentucky

Geological Survey, Map and Chart Series 27, Series XII, poster.

Mitchell,

Michael J., 2001, Soil Survey of

Paylor, R.L., Florea, L.J., Caudill,

M.J., and Currens, J.C., 2003, A GIS coverage of

sinkholes in karst areas of

Ray,

Joseph A., and Currens, James C., 1998, Karst Ground-Water Basins in the Beaver Dam 30x60 Minute

Quadrangle: Kentucky, Kentucky Geological Survey, Map and Chart 19, Series XI,

Mapped scale 1:100,000.

Thompson,

Mark F., Plauche, Stephen T., and Crawford, Matthew

M., 2003, Geologic map of the Beaver Dam 30 x 60 minute quadrangle:

Kentucky Geological Survey, ser. 12, Geologic Map 1, scale 1:100,000.

Woods,

A.J., Omernik, J.M., Martin, W.H., Pond, G.J.,

Andrews, W.M., Call, S.M., Comstock, J.A., and Taylor, D.D., 2002, Ecoregions of Kentucky (color poster with map, descriptive

text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, VA., U.S. Geological Survey

(map scale 1:1,000,000).

Copyright

2003 by the University of