KARST GEOLOGY

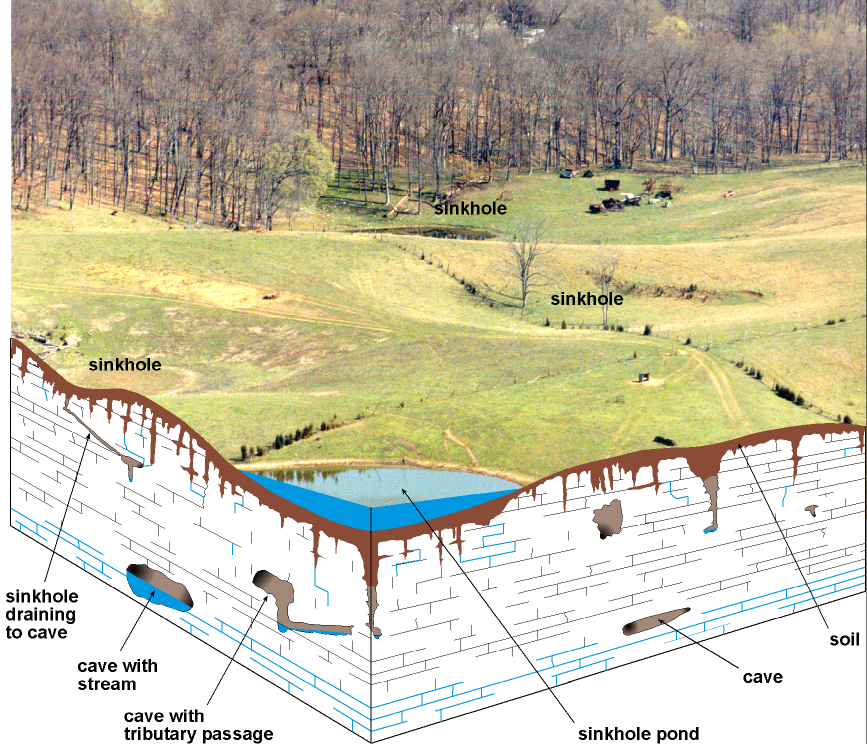

The term "karst" refers to a landscape characterized by

sinkholes, springs, sinking streams (streams that disappear underground), and

underground drainage through solution-enlarged conduits or caves. Karst landscapes form when slightly acidic water from rain

and snow-melt seeps through soil cover into fractured and soluble bedrock

(usually limestone, dolomite, or gypsum). Sinkholes are depressions on the land

surface where water drains underground. Usually circular and often

funnel-shaped, they range in size from a few feet to hundreds of feet in

diameter. Springs occur when water emerges from underground to become surface

water. Caves are solution-enlarged fractures or conduits

large enough for a person to enter.

ENVIRONMENTAL

PROTECTION

Never use sinkholes as

dumps. All waste, but especially pesticides, paints, household chemicals,

automobile batteries, and used motor oil, should be taken to an appropriate

recycling center or landfill.

Make sure runoff from

parking lots, streets, and other urban areas is routed through a detention

basin and sediment trap to filter it before it flows into a sinkhole.

Make sure your home septic

system is working properly and that it's not discharging sewage into a crevice

or sinkhole.

Keep cattle and other

livestock out of sinkholes and sinking streams. There are other methods of

providing water to livestock.

See to it that sinkholes

near or in crop fields are bordered with trees, shrubs, or grass buffer strips.

This will filter runoff flowing into sinkholes and also keep tilled areas away

from sinkholes.

Construct waste-holding

lagoons in karst areas carefully, to prevent the

bottom of the lagoon from collapsing, which would result in a catastrophic

emptying of waste into the groundwater.

If required, develop a

groundwater protection plan (410KAR5:037) or an agricultural water-quality plan

(KRS224.71) for your land use.

(From Currens,

2001)

CONSTRUCTION IN KARST

AREAS

Cover-collapse sinkholes

(outlined in red) are typical in areas of karst

geology. Many sinkholes such as these have not been mapped. The construction

implications of these features must be addressed for any type of development. Photo by Bart Davidson,

RESIDENTIAL

CONSTRUCTION

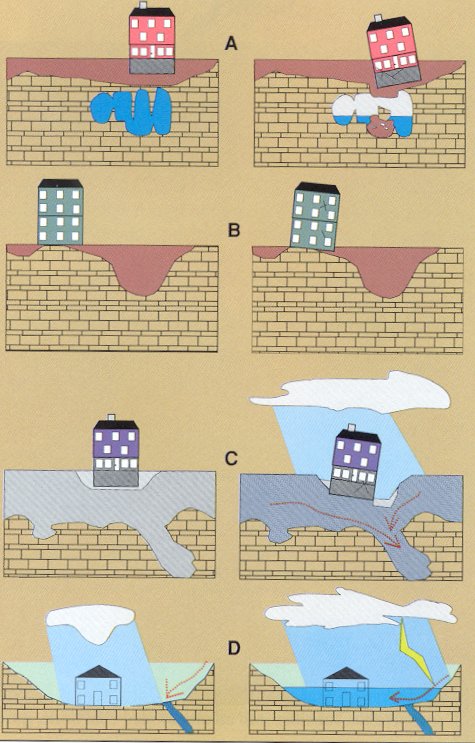

Limestone

terrain can be subject to subsidence hazards, which usually can be overcome by

prior planning and site evaluation. "A" shows construction

above an open cavern, which later collapses. This is one of the most

difficult situations to detect, and the possibility of this situation beneath a

structure warrants insurance protection for homes built on karst

terrain. In "B," a heavy structure presumed to lie above solid

bedrock actually is partially supported on soft, residual clay soils that

subside gradually, resulting in damage to the structure. This occurs where

inadequate site evaluation can be traced to lack of geophysical studies and

inadequate core sampling. "C" and "D" show the close

relationship between hydrology and subsidence hazards in limestone terrain. In

"C," the house is situated on porous fill (light shading) at a site

where surface and groundwater drainage move supporting soil (darker shading)

into voids in limestone (blocks) below. The natural process is then accelerated

by infiltration through fill around the home. "D" shows a karst site where normal rainfall is absorbed by subsurface

conduits, but water from infrequent heavy storms cannot be carried away quickly

enough to prevent flooding of low-lying areas. Adapted from

AIPG (1993).

RADON

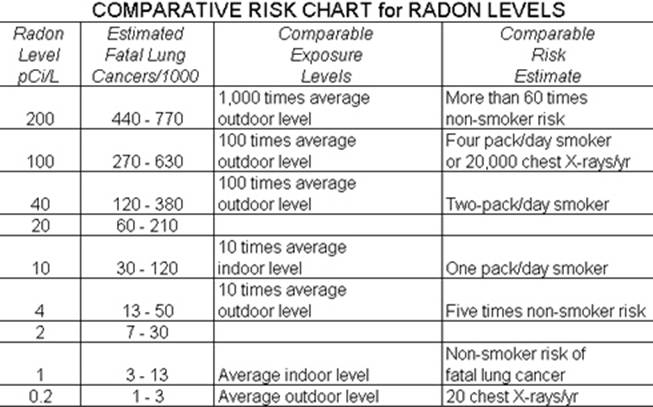

Radon

gas, although not widely distributed in

EPA

recommends action be taken if indoor levels exceed 4 picocuries per liter, which is 10 times the average outdoor

level. Some EPA representatives believe the action level should be lowered to 2

picocuries per liter; other scientists dissent and

claim the risks estimated in this chart are already much too high for low

levels of radon. The action level in European countries is set at 10 picocuries per liter. Note that this chart is only one

estimate; it is not based upon any scientific result from a study of a large

population meeting the listed criteria. (From the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency, 1986.)

EROSION CONTROL

During

construction, erosion-control fences such as these may be needed to prevent

silt from entering local streams. Photo by

Bart

Davidson,

Riprap

drainage control and erosion protection. Photo by Stephen Greb,

GROUNDWATER

In the central and

southeastern half of the county, about three-quarters of the drilled wells

yield enough water for domestic use. In low-lying areas, a few wells yield

adequate amounts of water for a domestic supply, except in the northwestern

corner of the county close to the

River. In the northwestern corner, most wells are adequate

for a domestic supply, especially from wells that penetrate small solution

openings within the limestone bedrock.

Springs are present

throughout the county, with flow rates ranging from several gallons per minute

to 670 gallons per minute. Some springs are sufficient to supply domestic

needs, but most go dry during extended dry periods in late summer and fall.

For more information on the

groundwater resources of the county, see Carey and Stickney (2001).

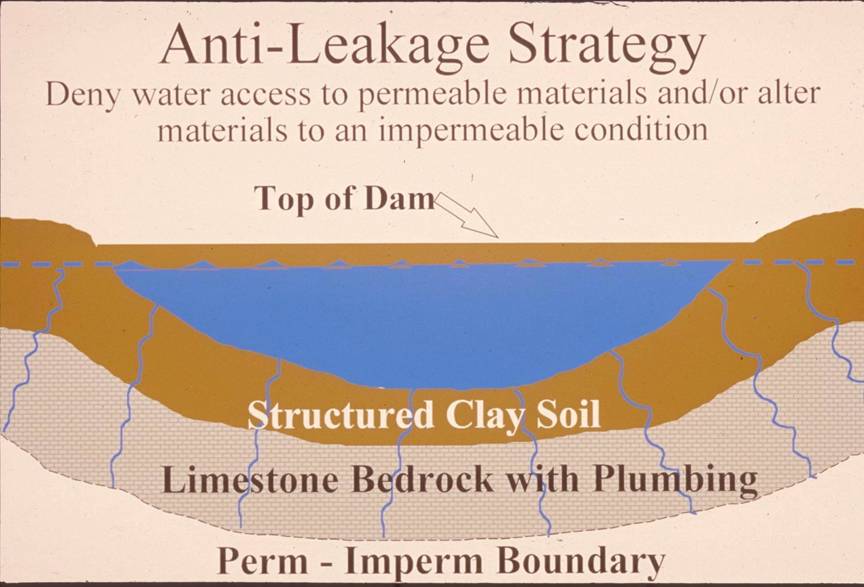

POND CONSTRUCTION

Successful pond construction

must prevent water from seeping through structured soils into limestone

solution channels below. A compacted clay liner, or artificial liner, may

prevent pond failure. Getting the basin filled with water as soon as possible

after construction prevents drying and cracking, and possible leakage, of the

clayey soil liner. Ponds constructed in dry weather are more apt to leak than

ponds constructed in wet weather. The

Dams should be constructed

of compacted clayey soils at slopes flatter than 3 units horizontal to 1 unit

vertical. Ponds with dam heights exceeding 25 feet, or pond volumes exceeding

50 acre-feet, require permits. Contact the

WASTEWATER TREATMENT

Sewage lagoons are often

constructed near industrial facilities to aid in pretreatment. Dams and

embankments of lagoons like this one should be monitored for leakage, which may

migrate and affect local streams and groundwater. Photo by

Bart Davidson,

WASTE DISPOSAL

A large poultry processing

plant near

NATURAL RESOURCES

The lumber industry is a

common land-use feature of

MINERAL RESOURCES

Limestone is a major product

of

ENERGY RESOURCES

Oil and gas development in

TOURISM

76 Falls

is a scenic area adjoining

RECREATION

The land-use planning guides

on this map series take into account intensive and extensive recreation.